This is a live book review. I’m writing it as I read it.

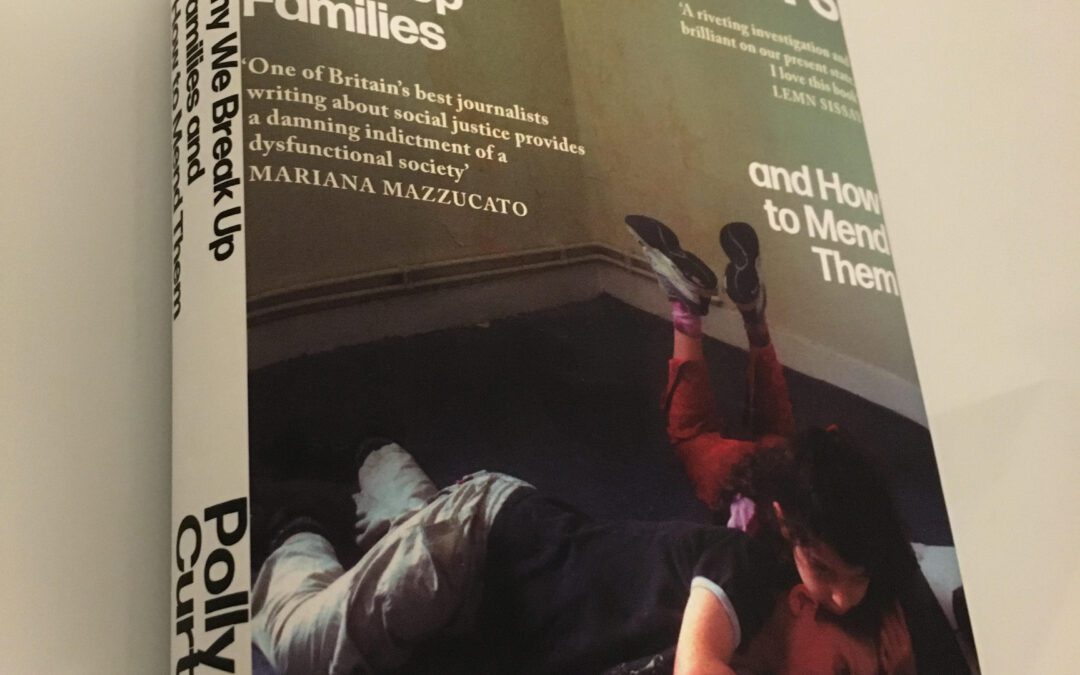

The book itself is a beautiful object. I don’t read enough books to know if this is typical for a Virago hardback, the latest thing in hardbacks, or just this book. This book feels pocket-sized. You’d want to slip it in your bag, almost in your back pocket and take it on the road like a little friend. You may also want to keep running your hand over its matt waxed jacket.

The cover is a ‘painting like’ photograph that somehow renders a stark scene visually compelling [*Updated]. An empty room, with cheap office-style carpet and damp stains in the corner, resonant of a social work office after years of under investment. Two children, perhaps 7 and 9, strewn across the floor on their bellies. Absorbed. Together. As if they grasp without words the need to hold on to each other. Perhaps waiting to know where they will go that night – they’ve done this before. Bodies lost into deep shadow, cheeks flecked with Rembrandt light cascading down from high windows. Stark white typography is branded over oatmeal walls, cobalt carpet, deep blue shadows and bright red trousers. The lettering is scattered around the book cover. Why We Break Up Families and How to Mend Them are separated from Behind Closed Doors and also from each other. Spilled to different sides of the cover. Each now isolated on the margins.

Right. I’m going to open up the cover and go inside now. Past the midnight blue of the inner page. To the people and their stories. And how Curtis marshalls these.

Curtis organises her look behind the curtains around the stories of the human beings at the heart of the child protection and care systems. She opens each chapter with a gripping individual perspective and springboards from there into the relevant research. From Caitlin, whose children were removed and adopted before she got far enough away from domestic abuse, to the education welfare worker battling to protect children that statutory services don’t reach, and the radical birth and adoptive mothers who ended up co-parenting. Showing then telling, again and again. With a final look at pioneering models for radical change and her own suggestions for reform.

Readers can’t hide behind ‘wow that’s compelling lived experience but it doesn’t really tell us what actually happens to most people most of the time does it?‘. Nor are they left feeling powerless to grasp the whole picture, let alone change anything in the face of a vast competing research base. Curtis has researched and synthesised it for us, bringing it together in one readable, beautiful, little hardback (or audio etc) – the lived experience, the research, the problems, and the potential solutions. Grasping the nettle of the problems and vulnerabilities we see featuring over and over in the lives of those whose children are removed. Keeping those people, the evidence, and social justice at the centre. All meticulously referenced by footnotes to extensive research. In featuring her own parenting story, Curtis breaks with the ‘us and them’ of author and subject, makes herself vulnerable, and denies reader temptation to ‘other’ the parents in these stories.

The book anchors itself on an informal estimate apparently given to the author by Keehan J, who is the chair of the Public Law Working Group, that removal may have been unnecessary for as many as 27,000 of 80,000 children in care, had the right support been in place at the right time.

We are removing too many children from their parents. We are not giving families a chance to stay together. It’s an open secret within the system (Curtis, pages xiii & 63-64).

Going on to argue, through the stories featured and the research highlighted, that this is:

…a system riddled with class bias and prejudice against different ethnic groups and people of different abilities; it is a system that punishes isolation, focuses its powers on marginalised, vulnerable women and dismisses and ignores fathers. Communities who are subject to the system know this and it has eroded any trust there was.

Curtis doesn’t shy away from the contradictions. Chief amongst those being evidence both of dramatic interventions to whip a child out of their home [and also] of years of failure to intervene and support them to stay there safely. Concluding (as others have before) that:

What underpins these extremes is the eroding of the state’s ability to make the hardest decisions well. So we leave too many children in danger, and we remove too many because we didn’t intervene earlier or have the confidence to assess risk and support them to stay there safely. [My emphasis]

Nor does she shy away from evidence of drivers beyond poverty and austerity in recent rising care numbers. Including changes in societal definitions of (and tolerance for) child abuse, and risk aversion. Or the need to balance sustained, early support with decisive intervention when necessary, given children’s key developmental time windows for life. Nor that for some children, going into care is a life changer – or a life saver.

Curtis confronts misogyny and also class. She grapples with tensions between twin struggles – neither to fail children by writing safe fathers out of their lives prematurely, nor by minimising the risks some fathers pose.

But the unashamed focus of this book is on unpicking what is going on with Keehan J’s group of children – the estimated 30% of children in care who arguably may have been safely diverted away from care and dealt with by local authorities working with families if councils were properly resourced to act before issuing care proceedings. (p.64)

The book tells stories that may shed some light, showing a ‘system’ welded to profound social injustice both in terms of cause and solution. Curtis argues that racism, ableism, austerity and poverty created outside in wider society play out, with particularly devastating effect in the lives of certain children and families behind the closed doors of social services offices and the family courts, in removal and adoption of children.

She structures her ‘un-pickings’ through four sections: How it works, What’s really going on, Consequences; and Is there another way?

Confronting the need to get back to human emotions like love and loneliness, too often taboo in the language of family justice and social work, she ultimately concludes that real solutions lie in a strong supportive society fuelled not by process and defence, but by love.

Behind Closed Doors navigates problems with child protection social work and the family courts without blame, never losing sight of the systemic, accidental nature of their failings. It is systemic in analysis and solutions-focused in aim.

The sheer range, in a book this size is extraordinary. The relevance of the material selected is on point. Curtis skips through child development, brain development in infancy, attachment theory, the impact of poverty, race, class, disability and location on a child’s chances of staying with a parent or family member, adoption targets, repeat removals, basic explanations of the law and procedure behind removing children, social work models, contextual safeguarding, theories of change, risk aversion and the political and media context of the fall out from the death of Peter Connelly, the Care Inquiry, transparency, privacy rules and public confidence, the impact of care, and radical family centred models of intervention.

As remarkable is Curtis’ commitment to writing for everyone – sector professional or interested member of the public. Occasionally nuance and understanding seemed lost in the necessary cull to brevity – in the explanations of attachment theory and coercive and controlling relationships, for example.

Curtis succeeds in unpick[ing] the elements that have led to the removal of so many children from their parents and families and understand[ing] what it tells us about the kind of society we live in.

The book is a call to arms against the growing injustice of a system that, blind to poverty and inequality, holds individuals accountable for societal failures, and women in particular responsible for those failures to tackle male violence and abuse. It’s a book for those who have lived it. A book for those who struggle to continue to work within a ‘system’ that helps much less, and harms much more than it should or needs to. And a book for those who’ve been waiting for an accessible way to investigate the care system.

Whilst many have made these cries already, Curtis packages them up accessibly and amplifies them as journalists do best. Out of the margins of hidden personal experience and calls by campaign groups, out of the dry corners of journals and research reports, from behind the closed doors of social services and family court privacy rules – and into the mainstream.

I hope these stories, this analysis, and these proposals for change do make that leap.

I hope the force of public opinion does drives the change that children and their families have long cried out for.

Not only will I keep the book. I will recommend it to others. In fact I may send a copy to my MP and encourage others to do the same. Just as others did Jane Monckton-Smith’s game changer on understanding the role of control in domestic homicide. These are the two most useful non-fiction books I’ve read for quite some time.

Behind Closed Doors. Why we Break Up Families And How to Mend Them – Written by Polly Curtis and published by Virago Books, launches on Thursday 3rd February 2022. It’s available for order here. Use code SOCIAL22 to also register here for a free Tortoise Slow Media Think-In on the future of social work, After Arthur Labinjo-Hughes, Peter Connelly and Victoria Climbié: what should social workers do?

[Transparency note – One of the stories Curtis tells is that of barrister and Transparency Project Chair Lucy Reed]

[* I wrongly attributed the book’s cover image to photographer, Tom Pilston. It’s from Alamy. Pilston did the author’s photo].

We have a small favour to ask!

The Transparency Project is a registered charity in England & Wales run largely by volunteers who also have full-time jobs. We’re working hard to secure extra funding so that we can keep making family justice clearer for all who use the court and work within it. We’d be really grateful if you were able to help us by making a small one-off (or regular!) donation through our Just Giving page. You can find our page, and further information here.

Thanks for reading!

I know people have to keep talking about this and Journalists must keep writing about what is happening and I thank Polly Curtis for this book and highlighting the terrible injustice to children and their families that is taking place in Family Courts but at the same time I despair that another Journalist’s words will fall on deaf ears.

Can someone write and tell us, us being the families that have been affected and traumatized, when the government have listened to Journalists and when the major overhaul of the ‘system’ is going to start?