I’ve just had another go at testing open justice in the family court through legal blogging. The aim remains to identify and work through any barriers created by the move to remote working in response to Covid.

The pilot rights and open justice

Legal bloggers have a right to sit in on otherwise private family courts hearings, just as journalists can (the Family Procedure Rules are amended by Practice Direction 36J PILOT SCHEME: TRANSPARENCY (ATTENDANCE AT HEARINGS IN PRIVATE)). In cases concerning children, neither category of reporter can publish anything substantial from hearings without permission from the judge. The pilot falls for renewal again on 30 June 2020, having been extended once. It also falls within the ambit of the President’s current transparency consultation. [Update – its been extended see here]

The right gives effect to an important underlying principle: That, even though family justice operates on a more private basis than other types of hearings, due to the nature of the subject matter and the vulnerability of those involved, it should still be delivered as openly as possible. You can read all the posts The Transparency Project has been able to write as a result of the pilot here.

The pandemic

Scrutiny of the family courts is all the more important right now precisely because of the unprecedented pressures both those seeking justice, and those trying to deliver it, are under due to Covid. (And because of the need to ensure that emergency interim measures do not become our default mode, with open justice the casualty of that, given the dramatic acceleration of a pre existing and partial HMCTS digitisation roll out in response to the pandemic. See here from MacDonald J).

This hearing

Just such intense Covid related pressures were apparent in this hearing. In the lives of the family concerned, (who will already have been under intense pressure pre-pandemic, from the care proceedings and the vulnerabilities that led to them). And also observable in the justice system itself – under-resourced and straining at the seams in terms of capacity, even before Covid.

This was a mother’s last minute application to adjourn a final hearing of care proceedings on the basis of fairness, listed urgently by those on behalf of the child. The 7 year old child concerned had remained in her mother’s care at her parents’ house throughout the proceedings, which means the court must have accepted that the child didn’t need an immediate separation to secure his safety. Nevertheless, the local authority was now saying that the child’s needs couldn’t be met by remaining at home in the long term. The Cafcass guardian’s evidence was not yet available (in the absence of clarity about the hair strand testing), so her view was not yet known. The mother seemed to be the only family member party but didn’t attend the virtual hearing. It wasn’t clear to me why that was.

At stake was the fairness (or otherwise) of having a final hearing without the mother having had the hair strand tests the allocated judge had said the case needed when he made a direction to that effect at an earlier stage. The mother said she hadn’t been able to be tested because of Covid restrictions.

Another issue was the type of final hearing that was appropriate in the circumstances of this case. (See The Road Ahead, 9 June 2020, and this recent judgment of MacDonald J for recent judicial thinking.) On how judges should best juggle the competing demands of fairness to a parent, public safety, speculation on lockdown easing, and avoiding delay for children – in order to decide whether to adjourn a final hearing, press on remotely, or try to find some hybrid half way house solution.

- Could a way be found for this mother to be safely present with her legal representative to give her evidence away from a cramped household, that included her 7 year old child and her parents (who had Covid symptoms and were awaiting test results)?

- Should the court be asked even to contemplate a safe physical hearing, given there were symptomatic people in the mother’s household? The Judge said otherwise and reminded also that local safety protocols required significant notice for safety planning even for suitable cases.

All this was made harder as the allocated judge wasn’t hearing this application and this judge and parties thought there must have been an oversight in failing to grapple earlier with deciding the right type of final hearing.

Ultimately, both decisions were put over to the first day of the final hearing for the allocated trial judge to make, on the basis he would know about the earlier thinking and would by then have the benefit of the guardian’s analysis. In addition the judge said that other things were needed before sound decisions could be made on whether to proceed – written updates from the hair strand test providers on what could or could not be done by when and why; medical evidence about the Covid household situation; and position statements from the parties – including detailed, practical proposals for this mother being able to attend her legal representative away from her home for at least some if not all of the hearing, including her own evidence.

Barriers

Court Lists

The first barrier was one I anticipated. Last time I attempted legal blogging of a remote hearing I chose a 2pm hearing knowing it would likely be impossible to chase through the administrative steps between the publication of court lists in the late afternoon and the start of the remote hearing platform by 10am the next day. One has to identify a hearing, contact the court (having found a generic email address for the relevant court as the lists do not usually provide contact details) to ask for notification and information to be sent to the judge and ideally also the parties, and follow up when the court don’t get to the email in time due to the amount they are processing. This time I selected a 10am hearing to test if this would happen.

I chose Reading Family Court (RFC) because their CourtServe online lists helpfully specify when a hearing is remote in a way not all other lists do. They even specify the remote platform being used. They also (unusually) provide an email address and phone number for reporters and others wanting to attend a remote hearing. I wanted to try the HMCTS flagship CVP platform that has just started rolling out in the family courts and knew RFC were piloting it. RFC was also identified on CourtServe as the admin hub for requests to attend all South East Courts. Moreover, His Honour Judge Moradifar, regular publisher of judgments transparently at BAILII was the Designated Family Judge (DFJ).

The RFC lists eventually went up about 5.30pm. I chose a directions in care proceedings hearing listed for 10am the next day and emailed asking to attend. This was necessarily out of hours. I rang the court office at 9am the next day to follow up. I could only get an ‘all operators busy please re dial later’ with my call then cut off, even when selecting the ‘stay on the line for same day urgent matters’ option from the automated menu. RFC were plainly operating beyond capacity. If I hadn’t been able to ask a lawyer for the judge’s direct email (and most journalists and legal bloggers can’t most of the time) and write to him directly around 9.15am, my open justice foray would have ended there. As it was I had a pretty quick response from the judge’s clerk with log in details on the basis it was not yet agreed I could join, and also received a prompt to use them just before 10am.

Attending

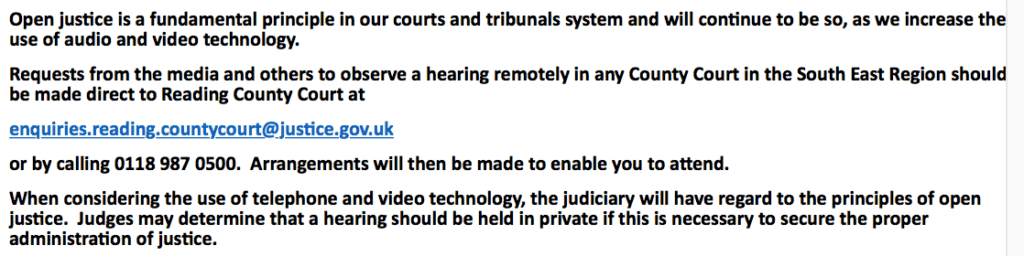

I expected to find procedural barriers and IT teething problems, but the new notice (below) on the listings of Family Court hearings in courts piloting HMCTS’s platform of choice – CVP – was puzzling:

It’s great that this message acknowledges open justice as a fundamental principle, and that it provides contact details. But the notice also seems to muddle a decision to sit in private with a decision to exclude the press and with the right of journalists and bloggers to attend an ALREADY PRIVATE hearing. It should perhaps say that the court may exclude observers where necessary to secure the proper administration of justice. The proper administration of justice (the actual wording is for the orderly conduct of proceedings or if justice will otherwise be impeded or prejudiced) is one among three reasons specified in the family procedure rules for excluding a reporter where necessary for case specific reasons. The others are the interests of a child or safety of a party/witness.

I was asked to sign in remotely and then held in a virtual waiting area. I initially wondered if I’d been waiting while the Judge consulted with the parties in a preliminary hearing before suddenly some 10 minutes later, I was in, at the start of the substantive hearing, with my presence recorded as ‘by consent of the parties’. In fact I later learnt from correspondence that we’d all been waiting not just me. My email hadn’t reached the parties ahead but the judge had emailed to alert them ahead and no one had objected.

Technology

Before we even got to that bit it took about 15 minutes to get everyone logged on. The social worker was appearing as ‘guest’ and eventually emailed to say she couldn’t see or hear even when showing as logged in on the CVP platform court end. Her web browser was apparently saying the server IP address couldn’t be found. Counsel for the Local Authority took the lead, alongside the court clerk, notwithstanding that he wasn’t the ‘host’, getting the social worker dialled in so we were ready for the judge. There was also considerable noise interference until the clerk was eventually able to mute her microphone, but she was quick to reassure and explain when I asked.

Documents

Last time I wrote about my legal blogging experience I said that next time I’d ask for documents, and this time I did so in my original email to the judge that I asked to be forwarded to the parties. Seeing the position statements that had been filed would have helped me grasp the issues more clearly so as to follow and report with accuracy. But the race to even get in and on, and trying to fathom how my application had been treated procedurally, took over, and I parked that for now.

Permission to report – the S.12 barrier

There have been some calls recently for the inspiring work Celia Kitzinger and Gill Loomes are doing in the Court of Protection, to facilitate and scale up observation by the public, to be re-created in the family court. But the issues and barriers are very different (albeit there are a few common problems, such as listing).

The starting point in the Court of Protection is that hearings are held in public, and so anyone may attend to observe. This starting point has been reversed temporarily for remote hearings, due to the pandemic (Para 57 Remote Access Guidance), meaning that the public may now ask, and a judge may view a specific request favourably in light of open justice, and exercise her discretion to permit access. Because the Court of Protection generally sits in public there are none of the restrictions on reporting that apply to private Family Court hearings, apart from a bar on identifying the people at the heart of the case, and even under the current arrangements this position appears to be unchanged for observers who are granted access. The starting point for family court hearings is that the public can’t attend, which isn’t about to change. Only accredited media representatives and duly qualified legal bloggers can attend. This means that s12 Administration of Justice 1960 applies, and that has the effect that nobody can then report anything of substance as to what went on so as to evaluate it, critique it or comment on it, without specific judicial permission (after parties have the opportunity to argue otherwise) even if they don’t identify the family.

Overcoming the s.12 barrier, as things stand now, means deciding there and then during a hearing (while also listening and taking notes) what is going on, what you might thus want to write about, whether s. 12 prevents you, and what you can realistically ask for permission-wise and why. And it’s hard to interpret S.12 at the best of times.

The real barriers to scaling up the scrutiny that journalists and legal bloggers can provide in the family courts are less about showing journalists and bloggers what to do or how to get the listing, and more about addressing the big systemic factors that mean very few are willing or able to attend: from the operation of s.12 to the economic environment for journalism and small public legal education charities (when we go legal blogging we do it on our own time). Complexity, potential conflicts of interest, perceived professional risk, and professional time demands also prevent individual lawyers from feeling able to take time out as legal bloggers.

At this hearing, I drew up my wish list as we went along, and butted in politely at the very end to ask to share it. There were no objections to it but I was asked for blog copy ahead for the local authority client to agree, and the Judge on this occasion was keen on that option too. I’m still trying to get my head around where the line would fall between a sensible joint endeavour to check the terms of an intended s. 12 relaxation, and risk of improper inhibition or interference in a reporter’s freedom to critique. I suggested copy ahead wasn’t necessary, having defined my wish list quite specifically but the judge didn’t agree on this occasion. He and the LA representative were alive to the issue, emphasising that the request was just about s.12, and about enabling everyone to work through a process and learn together. Permission was granted subject to agreement of the parties, on seeing copy ahead. Which of course also left me free to potentially report more than my initial stated wish list.

Through correspondence after the hearing, those on behalf of the guardian asked for a small factual correction and a small addition, (disclosing information about how and why the directions hearing came about that I wouldn’t have known without sight of the position statements), before consenting. I was happy to make those changes. Those on behalf of the local authority were content with the way the substance of what went on before the judge was described in the blog copy for the purposes of relaxation of s.12. They also shared some procedural information that fell outside of the ambit of s.12 in case it altered some of my analysis, and shared some thoughts on how to read listings and overcome practical barriers.

Solutions

Listing

There’s been a positive shift recently in judges labelling published judgments by the type of case and key issue it raises rather than just letters of the alphabet. It’s a big bonus for transparency. There’s no reason why court lists can’t also improve too. A simple code to interpreting them placed at the foot of the lists would be a great start. For example, I have come to learn that a C in a certain place in a case number means care proceedings, but many journalists won’t know. And as counsel for the local authority later explained in correspondence – the first two letters (here ‘RG’) indicate the court location, Reading; the next two (‘20”) tell us the year of issue; the capital letter that follows (‘C’) denotes the type of proceedings (‘C’ is Care; ‘P’ is private law, ‘F’ is Family Law Act 1996 etc); and the remaining numbers indicate the number of cases issued ie. ‘00224’ means this case was the 224th care case issued in 2020.

It’s hard to see how RFC and others can realistically provide a number or email that will be responded to in time for a hearing the next morning, given the pressure they are under. But it’s a question worth asking. I’ve had some email exchanges with RFC on this now. Their initial response was that we should simply provide more notice. That works when you are targeting a high profile case and seeking the listing ahead as we do regularly already. But it’s no solution to the legitimate public interest in also observing on an ad hoc basis. (I’m now wondering if there might be scope for reporters to be able to access and use a list of judge’s emails where unable to provide the sort of notice that going through the court office requires). Once the message gets to the judge, the process seems to work very well and my experience is that judges so far (having opted for circuit judge level and above) is that they are welcoming and not defensive, despite the pressure and vulnerabilities affecting the system.

Without doubt there were frustrating IT glitches that cost perhaps 15 minutes in court time while the clerk and LA legal rep sorted them. But a pilot is at least in theory a method to sort out such issues, one assumes.

The S.12 barrier

Our thoughts on the complex issue of how this barrier might change and why are in The Transparency Project’s detailed response to the President’s consultation on transparency.

Unfamiliarity and scaling up

Unfamiliarity with journalists and legal bloggers who rarely make it in to the family courts is a barrier. Overloaded practitioners are sometimes unfamiliar with the law and the procedure (and legitimately focused on the bigger picture of the actual case decision with all the difficulties that involves). That can translate into cautious, even defensive practice, particularly on the part of local authorities where those giving instructions are at arm’s length in large, cautious, bureaucracies.

The Transparency Project pioneered and drove the legal bloggers pilot into existence. We have also long tried to encourage and enable journalists and legal bloggers (as well as legal professionals who suddenly find a legal blogger in court). We will continue to.

The new transparency notice

As to the transparency notice, I’d like to think it could be improved further by tweaking for legal clarity, adding some sort of key to reading listings, and providing a workable method for ‘reporters’ to access hearings even at relatively short notice. What was apparent from the judge was an openness to working with legal bloggers, and a judicial steer towards us all learning together on open justice under a pandemic.

We have a small favour to ask!

The Transparency Project is a registered charity in England & Wales run largely by volunteers who also have full-time jobs. We’re working hard to secure extra funding so that we can keep making family justice clearer for all who use the court and work within it.

We’d be really grateful if you were able to help us by making a small one-off (or regular!) donation through our Just Giving page.

Thanks for reading!