Giving the second of a series of lectures at Gresham College on the difference between crime and family law proceedings, Jo Delahunty QC spoke about the use of expert medical evidence in cases concerning the death or serious injury of a child. She explored, by way of example, one of her own most challenging cases, that of baby Jayden Wray, in which severe rickets and vitamin D deficiency could have accounted for what at first seemed a case of gross abuse. Despite an acquittal in the criminal court, it was only after a hearing in the family court (in which Delahunty appeared for the mother), that the bereaved parents were finally exonerated.

How the case was reported before (left) and after (right) the criminal and then family court proceedings. (Screenshots via Jo Delahunty QC’s lecture slides, reproduced with thanks.)

Crime and punishment

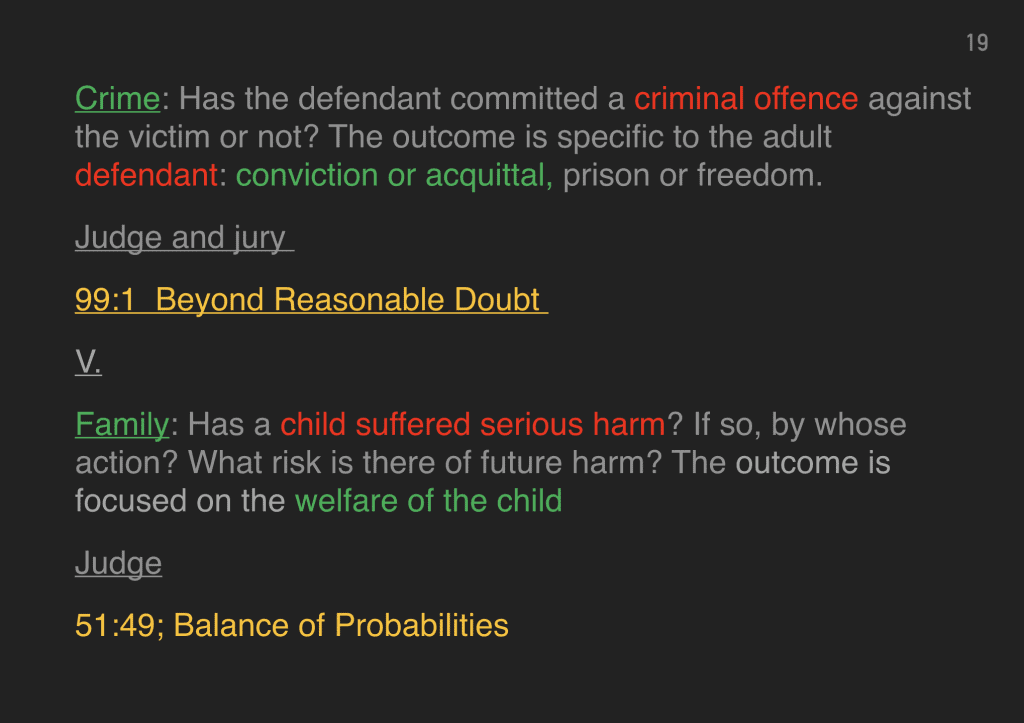

Tonight’s lecture was the second in a two-part exploration of the ways in which a criminal court and a family court each deal with events concerning the same child victim and the same alleged abuser/s. The first lecture, When Legal Worlds Collide, explained the basic differences in the legal framework between

- the criminal justice system, where the burden is on the prosecution to prove the guilt of the defendant, to the higher standard traditionally expressed as “beyond reasonable doubt” (99:1) and where the focus is on the perpetrator and whether or not they require to be punished; and

- the family justice system, where in care proceedings the burden is on the local authority to show, to the lower standard of a “balance of probabilities” (51:49) that the child/ren have been subjected to and/or are at risk of significant harm and it would be in their best interests for a care or supervision order to be made. Here the focus is on the needs and interests of the child, not the potentially guilty person/s.

The difference in the purpose and the approach of the two systems accounts for the way, in some cases, a person may be acquitted of having harmed a child because the jury in the Crown Court is not satisfied so that they are sure (beyond reasonable doubt) of that person’s guilt. Yet the same person may be found, by a single judge sitting without a jury in the family court, to have been liable for harm and/or likely to cause harm to the child/ren whose best interests therefore require intervention by the state to protect them.

This first lecture also explained who can attend the two different types of court hearing. In crime, cases are heard in public and the press can report what happens subject to rules designed to prevent the risk of prejudicing the fairness of the trial. In family cases, the public is usually not admitted, and accredited media representatives can only report subject to restrictions imposed by the court, principally to avoid identification (directly or indirectly) of the children whose interests are concerned.

The first lecture then went on to discuss, among other examples, the well known case of Poppi Worthington (which has been in the news again this week, over the failures of the police investigation : see BBC, Poppi Worthington: Cumbria Police failed in toddler death investigation). In that case the father was found, by the judge in the family court in care proceedings, to have perpetrated a sexual and physical assault on the baby, but the Crown Prosecution Service decided there was insufficient evidence to warrant a criminal prosecution. (We have written about this case in earlier posts on this blog, see most recently: Poppi Worthington – legal aid, which links back to earlier posts.)

The key differences between the two systems are explained in this slide.

A shaken baby or benign cause mimicking abuse?

The second lecture, Guilty until proven innocent?, was concerned with the situation where injury or death appears to be caused by non-accidental head injury — often categorised as “shaken baby syndrome” — but can also be explained by a rare and unforeseen medical condition, such as the severe rickets and vitamin B deficiency found in the case of the baby, Jayden Wray, who was brought into hospital by his parents and died some hours later.

The problem with using a term such as “shaken baby syndrome” is that it presumes a cause. Typically, the NAHI (non accidental head injury) it refers to can be associated with three classic signs (the “triad”):

- Subdural haematoma (bleeding between the brain and the skull)

- Retinal haemorrhages (bleeding behind and within the eyes)

- Encephalopathy (brain dysfunction, swelling)

NB. This triad is a hypothesis not a diagnosis.

In the case of the baby Jayden Wray, these symptoms were present. But although they were explicable, and were assumed by some (including the police) to have been caused by, physical abuse (such as shaking) by the parents, they were also consistent with severe vitamin D deficiency and rickets. That was the opinion of the paediatric pathologist Dr Irene Scheimberg, who performed the post mortem. She snapped one of the ribs during the post mortem examination to assess its strength and found it to be extremely brittle. It transpired that Jayden’s mother, Chana al Alas, had a severe vitamin D deficiency and Dr Scheimberg contended that this had been passed to Jayden in utero, leading to congenital rickets.

But the cause of death was disputed by Dr Cary, the forensic paediatric pathologist instructed by the police, who concluded that Jayden had died of non-accidental injury. Despite their protestations of innocence, the young parents (16 and 19) were charged with murder and causing or allowing the death of a child. The trial did not take place for another two years, but in the meantime they could not return to their flat because it was the scene of a crime, and their names and faces were plastered all over the media.

So this, said Delahunty, was the situation:

Consider: a dead baby, a young couple, the mother mourning her dead son, pregnant, facing a murder charge and proclaiming her innocence and that of her partner.

Question: had this baby been born to a couple too immature to handle the responsibility and demands of parenthood? Shaken him? Hit him? Thrown him? Fractured his skull? Caused catastrophic injuries to his brain with footprints of abuse left behind by bleeding around his brain, his eyes and multiple fractures to the bones of his body?

Or were their protestations of innocence genuine?

If so, how to explain the multiple injuries he had suffered?

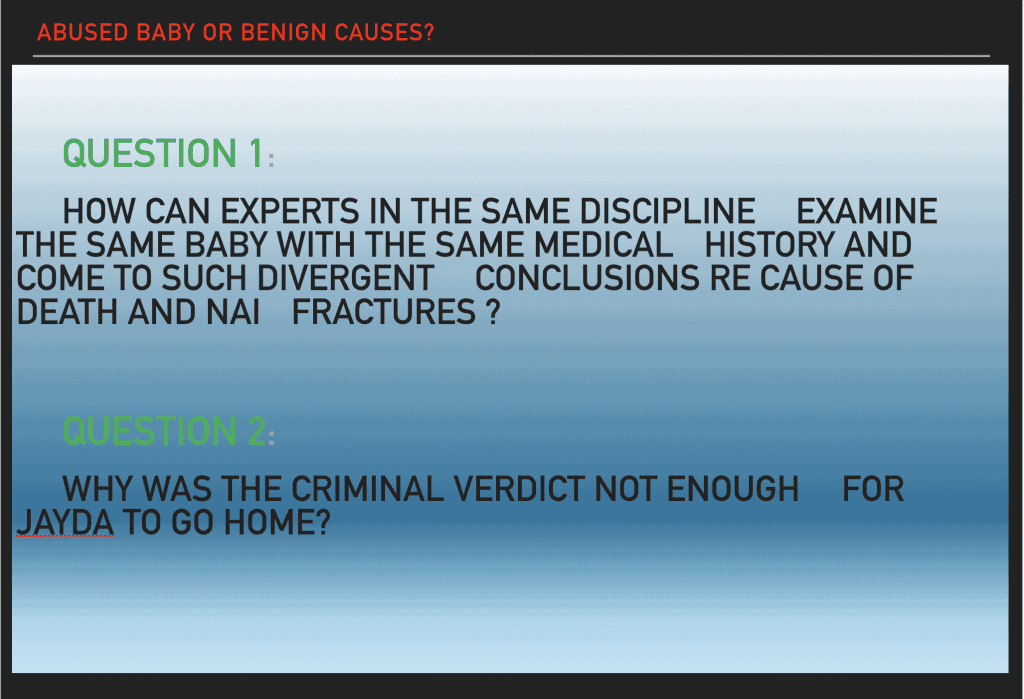

In the criminal proceedings, the Old Bailey court heard that Jayden died from brain damage and brain swelling but nearly 60 medical, professional and expert witnesses were unable to agree the cause. The judge directed the jury to acquit the parents after the prosecutors withdrew the charges.

In the meantime, another child had been born, a little girl called Jayda, who was removed at birth under police protection powers. The local authority then applied for an emergency protection order, which (unlike police protection) is something only the court can order.

It is a common misconception that social workers can, of their own volition, remove a child. They can’t. It has to be ordered by a court after a full hearing in which parents, child and local authority are all separately represented.

The family court hearing, in which Delahunty represented Chana, was heard by Mrs Justice Theis. She had the assistance of more than 40 medical witnesses including eminent experts covering many disciplines, including paediatric pathology, ophthalmology, osteopathology, neuropathology, radiology, mechanical forces, midwifery, and paediatrics.

There was also video and CCTV footage of the parents’ progress from the GP surgery where they first reported their alarm at Jayden’s condition, to University College Hospital (UCH) and into its corridors, where Jayden was examined and treated (including unfortunate mistakes and delays) before being transferred to Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), where two days later he died. This footage showed, significantly, that Jayden had been conscious and alert, and not all limp, and had been fitting, all of which was inconsistent with recent traumatic inflicted injury.

It emerged that some of the haemorrhaging round the skull fracture occurred while Jayden was in GOSH, when his parents had no contact with him. On of the experts said he had not seen such severe rickets since the 1970s, and two others said that, as a result of the rickets, the fracturing could have been caused by normal handling.

Theis J had the advantage of hearing all the evidence and considering it in the round, which was a luxury not available to the clinicians and experts examining Jayden at the time. She concluded that she could not be satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that any of the injuries were as a result of inflicted deliberate harm caused to Jayden by either of the parents. Though long, the judgment is worth reading in full: see Islington London Borough Council v Al Alas [2012] EWHC 865 (Fam); [2012] 2 FLR 1239.

In conclusion Theis J observed [235]:

Despite the extent of the dispute between the various experts, the one aspect they were all agreed upon was the need for further research. In particular research in relation to the different aspects of the triad and the impact of Vitamin D deficiency and rickets on babies under 6 months. I wholly endorse that view.

After judgment was given (in public) the mother, Chana Al Alas, and the father, Rohan Wray, were reunited with their daughter Jayda, now 18 months old, who had been removed at birth and never lived with them. The case was reported in the press with a very different slant from how they had first reported it, as the two starkly contrasting screenshots of the Daily Mail at the top of this post demonstrate. (Note the needlessly prejudicial way in which a case of alleged “shaken baby syndrome” is reported in the first image.)

Two questions not addressed by the press, but hopefully now explained by Jo Delahunty in her lecture, were encapsulated on this slide:

Unknown cause?

In conclusion, Jo Delahunty made a number of general observations.

First, the family court is not a place where you can apply Sherlock Holmes’s dictum: “when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbably, must be the truth”. The child protection judge, lawyer and expert must be aware that the conclusion that a child has sustained injuries through an “unknown cause” is not a declaration of failure to find the cause and effect of the truth. There is no shame in saying we do not have all the answers.

Science is constantly evolving and miscarriages of justice have happened with parents wrongly accused of shaking their child to death based on scientific research and hypothesis, genuinely held, but discarded or refined as science develops.

That said, it is a sad fact of life that babies and children are hurt, and sometimes killed, by those who ought to protect them from harm. Not every claim to have been a victim of a miscarriage of justice is valid. The judge of the family court has a hugely difficult task to perform because the stakes cannot be any higher, for the surviving child, the parents and society at large. That burden is shouldered by the family judge alone: there is no jury to share the load.

Next lecture

Professor Delahunty’s next lecture, on 12 April at Gresham College, under the title Expert Witnesses: A Zero Sum Game, will further explore the role of expert witnesses in family court cases. All these lectures are part of a longer series entitled When Worlds Collide: The Family and the Law.

The above summary was written by Paul Magrath, who attended Professor Jo Delahunty QC’s lecture on Thursday, 2 March 2017. It is based partly on his own notes but mainly on the slides and lecture transcripts (for both lectures) which can be downloaded from the Gresham College website.

Note. Jo Delahunty QC will be chairing Transparency Project’s event, also at Gresham College, on 5 April 2017, Reporting the Family Courts – Are we doing it justice? (This is currently fully booked but there is a waiting list in case of returns.)

May I congratulate Professor Jo Delahunty QC on her tenacity for justice, exhausting reading, only wish there were more female, advocates and judges, in the family law system

Lack of comments you may think? comments are usually from parents that do not even believe the truth the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, ever sees the light in these courts, possibly the first honest case ever, pity other child representatives do not follow your lead