On Saturday 13 October, Families Need Fathers sent us a document called Analysis of Post LASPO Use of Non-Molestation Orders and said it was embargoed until the following Monday. On Monday morning, the Guardian published Parents ‘weaponising’ domestic violence orders, claims charity: Families Needs Fathers alleges non-molestation orders are being used fraudulently to obtain legal aid (Sub headed: Families Needs Fathers alleges non-molestation orders are being used fraudulently to obtain legal aid).

We weren’t surprised to see more from FNF who had long promised a response to our blog post Are Thousands Misusing Abuse Orders to get Legal Aid? commenting on their claims at BBC News and the Telegraph in July 2018. But we were a bit surprised to see the Guardian running exactly the same story as ‘news’ all over again, some 3 months later, with precisely no independent analysis of the claims or data just as BBC News and the Telegraph had before them. Did they not realise this story had run? Were they unaware of criticisms of the claims? Was the latest FNF press release just too enticing to those under pressure to fill column inches over and over?:

We googled ‘false claims of injunctions to get legal aid’ which seemed an obvious search term for any journalist investigating this. The BBC News report followed by our Transparency Project analysis of the claims were the first search items, so we can only assume the Guardian ran the story knowing it was neither new nor evidenced, and that they were simply parroting FNF.

What’s new in the FNF report?

We’ve always recognised that false allegations of domestic abuse (in so far as they occur) matter for (mostly) fathers and their children. We know that there can be unintended consequences from law and policy. We have always acknowledged that the questions FNF raise are worth asking. We agree with some of their recommendations. We share the view that removing legal aid from those accused of abuse has created some very real difficulties.

But what we’ve also always said is that these questions should be posed as questions, not fact, and the emphasis should be on how to obtain a clearer understanding and / or tackle any abuse better, without undermining the legitimate policy aim of getting protection and legal aid to victims of abuse.

It is an enormous leap from showing relatively small rises nationally in numbers of injunctions made (with some local variations) after changes in legal aid rules in April 2013 to claiming this as evidence of injunction applications being abused. It seems to us just as likely that women who are genuine victims of abuse may have simply become motivated to see injunctions through by the wish to obtain legal aid. Or some other reason. Or combination of reasons. The point is, we don’t know.

It’s encouraging that the new report is framed less in terms of conspiracy or discrimination and more of unintended consequences, and in its acknowledgment of [a]

…historic, understandable, focus on the experience and needs of those who have suffered terrible abuse, particularly that of women.

And the statistical claims?

The new FNF report (underpinning their press release) seems to admit that last July’s BBC News headline claim of ‘thousands misusing abuse orders to get legal aid’ was just BBC News ‘highlighting’ an FNF ‘estimate’. (The Guardian headline this time round is more measured). `The FNF report also rows back on the July claim of a 30% rise in non-molestation orders, after legal aid changes. There are no new national figures. Just new ‘analysis’ of the same June 2018 Family Court Quarterly Statistics, which FNF now say show:

- An immediate significant rise by 18.5% of 3,614 injunctions made, to 23,140 after the legal aid changes, following a steady period of decline; and

- an overall rise of 37.5%, in numbers of injunctions made, from the legal aid rule changes, to March 2018 (latest figures available).

Do the figures show an immediate spike of 18.5% after the rule change? And an overall rise by 37.5% ?

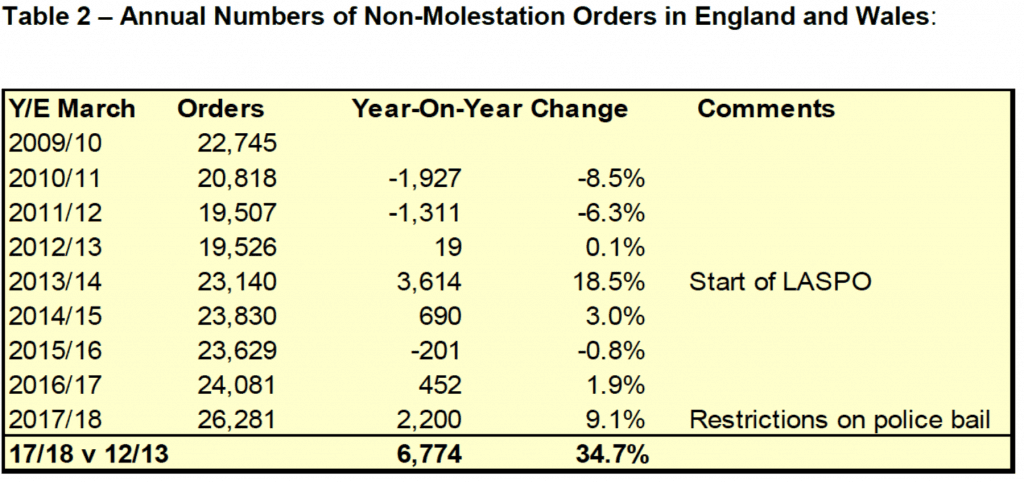

FNF rely on this graphic of isolated year-on-year Injunction Orders Made figures. It’s not an extract from the official figures but a table FNF have created FROM the official figures to reflect their own analysis:

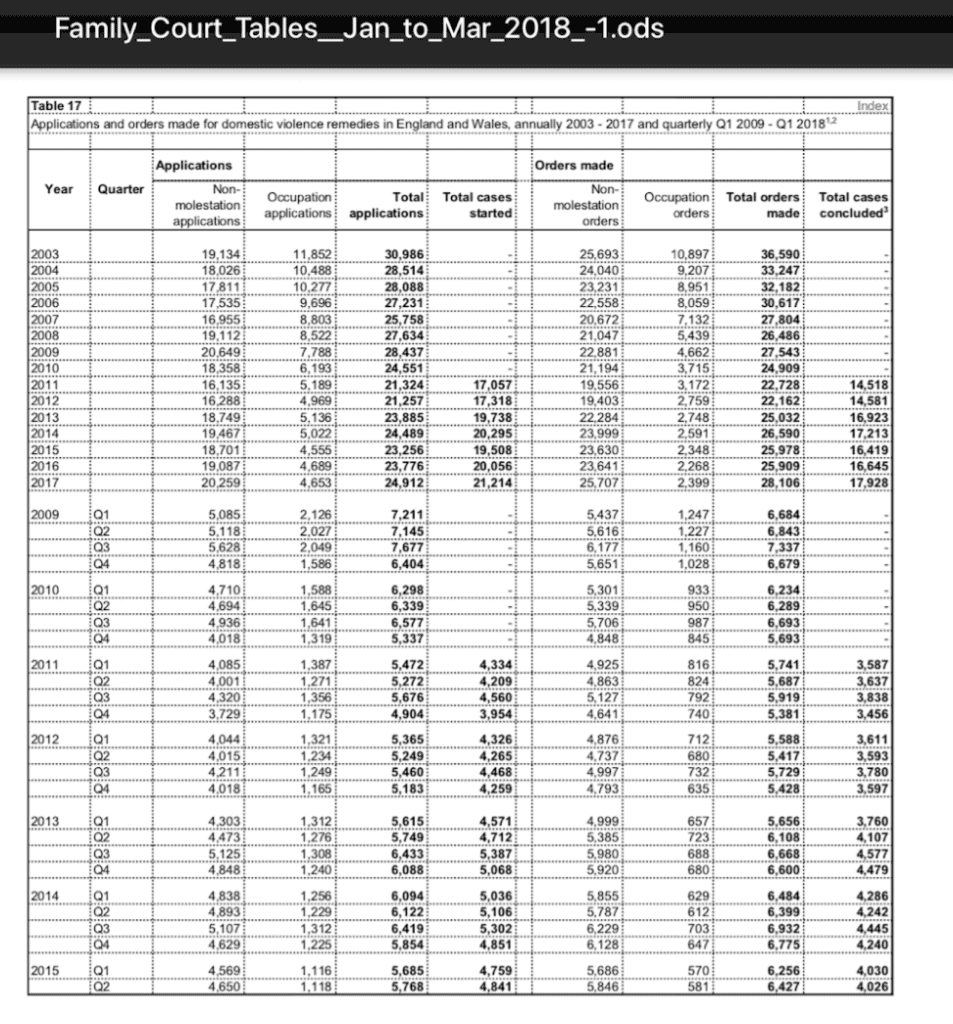

Table 17 of the June official Family Court Statistics Quarterly figures looks like this:

It’s divided into two sets of figures – injunction (NMO’s) applied for and those actually made. FNF only use the injunctions made figures. A quick look at those shows a rise just after the legal aid changes kicked in from April 2013 (Quarter 2).

But Table 17 calculates years in four quarters from January to December not to end March as the FNF created graphic does. So we don’t know how FNF calculated their figures of 19,526 NMO’s made (year 2012 to March 2013) and 23,140 (for the following year 2013 to March 2014) or how they reached the +18.5% immediate rise figure claimed. Nor how they calculated the overall rise figure claimed of +37.5%.

FNF also only include the years of interest to them. They don’t mention that the figures also show an injunctions made quarterly figure of 6,177 way back in the third quarter of 2009. This is a higher figure than in any of the 3 quarters in 2013 after the legal aid rules changed and even the first two quarters in 2014.

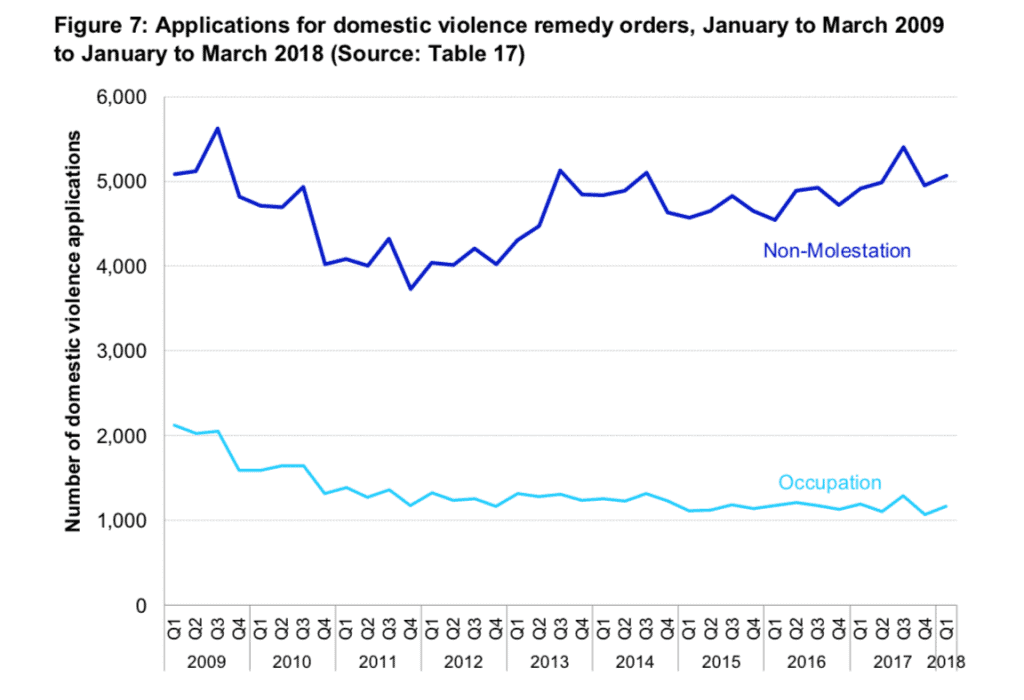

Or that the injunction applications made figures from Table 17 (with easy read headline graph reproduced below), also show a more complex picture. False and exaggerated claims for injunctions should show particularly well in the applications made data, since these should show rises across all applications (presumably including any weak, knocked-back applications that may have resulted from exaggerated applications alongside those granted). Yet applications for injunctions were starting to rise well before the legal aid changes of April 2013. They reached their highest in 2009 and then dwindled before starting to increase again from the last 2 quarters of 2012. Since then (with a relatively small spike soon after the legal aid changes), they have continued to steadily rise. (Including particularly sharply in 2017 as an intended result of the government widening the legal aid gateway evidence to make it less difficult for abuse victims to get legal aid). Applications made were higher in 2009 than they were either after the legal aid changes in early 2013 or even in the last full year of figures available – 2017.

Does FNF present any evidence of ‘fraudulent claiming’?

No. The allegations of fraud (whether by parties or by lawyers) made in the headlines and body of the FNF report are unsubstantiated.

Conclusion

FNF’s claims that thousands of people have been driven to apply for injunctions on false grounds by the removal of legal aid in 2012 are not backed up by the publicly available statistics. Regional variations, if they are significant, are always worth questioning, but there could be any number of reasons underlying these – there are no causal links shown by FNF between the volume of orders and aspects of local practice that can lead to any meaningful conclusions.

Featured Image – Creative Commons: Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0 Alpha Stock Images with thanks